There’s more to native breed cattle than meets the eye

By George Peart

Farm animal genetic resources are defined as “those animal species that are used, or may be used, for the production of food and agriculture, and the populations within each of them.” (fao.org, 2009). What exactly does this mean? In simple terms, they are the genetic sequences which code for our domesticated livestock species globally. These farm animal species are vital for the maintenance of global food security for future generations, and it is vital that genetic diversity is maintained so that we can further adapt our livestock to cope with future demand and environmental change.

Farm animal genetic resources are defined as “those animal species that are used, or may be used, for the production of food and agriculture, and the populations within each of them.” (fao.org, 2009). What exactly does this mean? In simple terms, they are the genetic sequences which code for our domesticated livestock species globally. These farm animal species are vital for the maintenance of global food security for future generations, and it is vital that genetic diversity is maintained so that we can further adapt our livestock to cope with future demand and environmental change.

In past decades UK cattle breeder preference has leaned towards continental breeds which are generally able to outperform the UK’s native cattle breeds in terms of milk yield for dairy cattle and carcase size and growth rate for beef. These preferences come as a result of market pressures forcing farmers to move towards a small number of cattle breeds in order to compete. Thus, cattle genetic diversity has been rapidly decreasing. This loss of diversity reduces UK cattle farming’s resilience to climate change but also means loss of culturally important breeds. These native cattle could also provide important DNA sequences to cope with external factors such as heat stress and tick-borne diseases. Furthermore, as breeders have been pushed towards highly productive cattle types, many of the hardier, upland breeds have been put at risk. In the past 10 years there has been a surge of research interest into preserving these native livestock breeds, thanks in part to the fantastic work of the Rare Breed Survival Trust.

Recent research into social factors and farmer motives for keeping rare and native breed cattle aimed to understand how and why these native breeds were being farmed in the UK. Prior to the survey, researchers thought that rare and native breeds were most commonly kept in small scale, subsistence farming systems. The results showed that while this is true, native breeds are also capable of providing larger scale business and land management opportunities in this country.

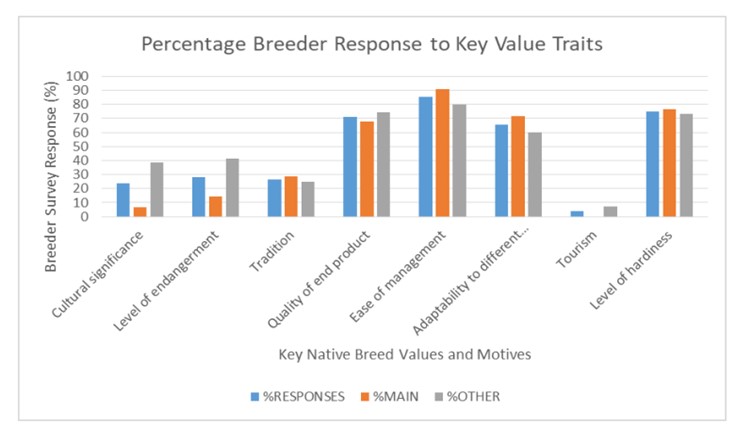

When analysing how breeder motives and values fit into this patchwork of farming systems, much less emphasis was placed upon traditional and cultural factors than expected. Indeed, all breeders prioritised private goods in the form of hardiness, product quality and management ease. When these options were removed and questions refocused on the priority of public goods, breeders selected genetic resource supply and adaptive traits over culture and tradition.

Figure 1: This graph summarises the reasoning behind survey participants choosing to farm with native breed cattle. The 162 respondents have been split into those which use farming as a main source of income (77) and those which have other sources of income (85).

These results blur the preconceptions that UK native breeds are farmed primarily on traditional values passed down through generations. Whilst tradition is still maintained, survey responses from all backgrounds suggest a forward-thinking mentality and emphasis upon using cattle for their utility to provide niche products. It is hoped that these conclusions set a precedent to reimagine how “FAnGR" conservation and breeding can provide for the UK’s economy and public. The transition away from the Common Agricultural Policy allows an opportunity for the public goods associated with native breeds and described in this project to be captured by UK markets.

George Peart is a member of the BSAS Early Career Council and a Graduate Management Trainee at livestock genetics company Genus Plc. His Master’s thesis focused on economic factors surrounding cattle genetic diversity in the UK. For more information please see the Rare Breed Survival Trust’s website: www.rbst.org.uk or get in touch at george.peart@genusplc.com All views are his own.