Shortening the restraint period of sows during lactation improves production and reduces stress in both the sow and her piglets

By Dr Katie McDermott

Limiting restraint time of the sow during lactation may enhance welfare, health and production of pigs. More time in the crate increased stress in sows which was reflected in her offspring.

With indoor pig production, the sow is often restrained in a “farrowing crate” during the lactation period. This crate allows the sow to stand and lie down, but otherwise her movement is restricted. Farrowing crates were designed to limit piglet mortality due to crushing by the sow, which represents a major economic loss and welfare concern. Farrowing crates also provide safe access to both the sow and her piglets for management. However, there is growing pressure to remove these crates in favour of either farrowing pens, where the sow can be temporarily crated, or loose farrowing systems where there is no restraint. This is due to pressure from the public and stakeholders to improve the welfare and health of the sow, whose natural behaviour is limited when crated.

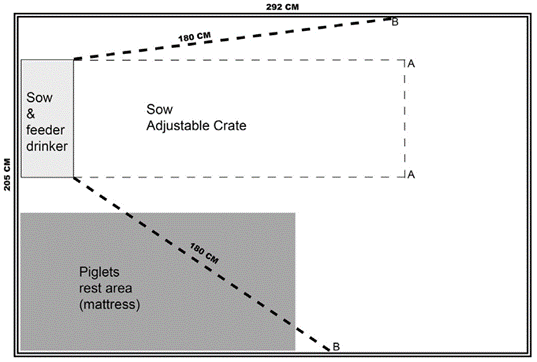

In a recent study, researchers modified traditional farrowing crates, so that they could be opened to allow the sow free movement from three days after birth (Figure 1). The group investigated the effects of opening the farrowing crate at different time points after the piglets were born. Sows were grouped into two groups for analysis based on when the crates were opened: short restraint (crates opened within 3-10 days of birth) or long restraint (crates opened within 13-24 days). Piglets were weaned at 24 days of age. A total of 77 mixed breed, mixed parity sows were used, and 997 piglets were born in this study.

Figure 1: A diagram of the farrowing pen used, taken from Morgan et al. (2021). At position A, the sow is crated. The bars of the crate can be opened up to position B where the sow has free movement within the pen. The piglet rest area cannot be accessed by the sow.

The study showed that for every additional day the sow spent in the crate, the weaning rate (which is defined as the number of piglets weaned divided by the number of piglets alive at 3 days of age) decreased by 0.4%. This resulted in more piglets weaned for the short restraint group than the long restraint group (10.4 vs 9.7 piglets, respectively). Both the sow and the piglets required less medication (e.g., antibiotics) when time spent in the crate was limited, although this was not statistically significant. Samples of hair were collected at the end of the study from both the sow and her piglets to measure cortisol, which can be used as an indicator of chronic stress. It was found that cortisol levels in the sow increased with the time spent in the crate and this was also reflected in the piglets.

Overall, this study showed that by releasing the sow from the crate earlier, welfare, health and productivity could be improved without impacting survival. Most of the piglet mortality occurred within the first 72 hours after birth, when all sows were still crated. As stress may negatively affect performance, reducing crating time of the sow may also improve the future productivity of her offspring.

For more information, the full article can be found in the journal Animal (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.animal.2020.100082)